On a sultry Sunday last year, I returned to Masjid, stepping off the train at Masjid station and taking the bridge that led me out west before walking up a gentle incline crowded by

paan-bidishops. Turning right I walked in the direction of the

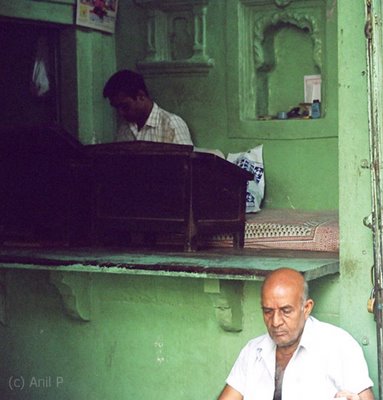

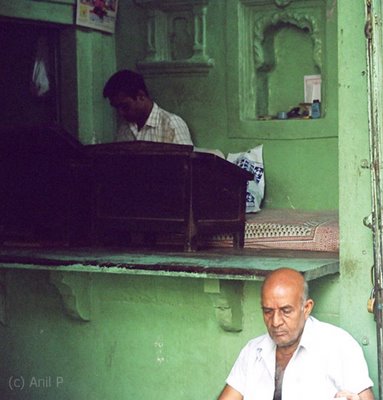

Bhat bazaar(rice market) whose history is almost as old as the history of Bombay itself. The narrow road led me past small shops that appeared to function as efficiently above the level of the road as below it. To conduct business with a shopkeeper of a basement shop, I had to bend and transact business through the narrow opening that opened out at the level of the road. I was none the worse for the effort. Above the shop sat another whose shopkeeper was oblivious to what was happening in the shop below his.

Walking through

Bhat bazar in Masjid near the Bombay Docks from where Indian Muslims set sail to the Annual Haj, I passed teams of local youth playing cricket in narrow lanes lined by old buildings on either side. Walking past them, and occasionally ‘sprinting’ up the wooden stairs of a building or two and speaking with curious residents emerging from darkened staircases or corridors that ran past their doors while dodging faint shadows, I soon realized that not all old buildings in Masjid now sport old names.

I meandered past

Ananth Niwas; opposite it an older building was simply named

Juna Ananth Niwas.

Juna in the local language, Marathi, and Gujrati, means old. It is possible that the older building was named

Ananth Niwas before the new one was built. Then, it was time for it to pass on its name to the new kid on the block, and acquire the prefix ‘Juna’. I would have thought that it might have been simpler for whoever it was that built the new building to have let the old building retain its name, and called the new building by a different name.

As I stood there and looked around at other old buildings in the

Bhat bazaar area, I turned my gaze once again in the direction of

Juna Ananth Niwas. I wondered if it was not the case that its residents on shifting to a new building did not want to let go of the identity the old one gave them, and the moments spent growing up in its embrace. There is no other reason I could think of. But this is not always the case with other old buildings there. On changing hands, some buildings in Masjid simply changed their names. Most old buildings change names more than once in their lifetime. The new name all but erases the old one even if the identity and the character of the building remains the same. In time when the older generation shifts to new residences or simply dies out, the old name goes out with them.

For the second time in two days, I took the stairs of the old building in the vicinity that sits unsteadily in the street in

Bhat bazaar. Across the building the fountain and the clock tower shone in the mid day sun. It took me a while to adjust to the lack of light in the short corridor that led to a flight of wooden steps. I looked up the staircase as it faded out in the darkness. Behind me the staircase appeared to descend tunnel-like to the street outside where a car sat on the kerb. There was no one around. The wooden steps were bunched up closely, overlapping one another. I’m accustomed to staircases whose steps do not overlap. It is easier to ascend staircases where each step ascends to the next at a right angle, leaving ample foot space with which to negotiate the steps. But here, in climbing up the stairs, I had to withdraw my foot from under the step protruding above before I could place it on the next step. Descending the steps became trickier still. On the way down, the steps do not begin from where steps above them end; instead each step begins from well under the step above it. After almost stumbling once, I took care to place my heel after accounting for the disconcerting overlap between the steps. This construct accounts for their steep descent.

Of the wooden staircases in old buildings that I’ve seen around Mumbai, their construction does not differ greatly. As I came up to the landing on the first floor, I was taken aback by rows of red lights from electricity meters glowing in the dark against a large board fixed to the wall. To its right, a window opened out on the street below. Behind me the staircase appeared to descend tunnel-like to the street outside where a car sat on the kerb. Strangely, for all the noise in the street outside, an eerie silence enveloped the building. It was as if I had stepped back in time, passing a corridor that connected different worlds, removing me from my surroundings. For a moment I hesitated, wondering if it would be wise to explore any further. However, it was difficult to resist the urge to explore the building, so I continued past the swarm of red eyes that seemed to circle maddeningly around themselves, vibrating to a silent melody in the darkened corridor, wriggling like fluorescent earthworms in a continuing nightmare.

I was yet to see any life in the building though the rooms that opened in the corridor ahead seemed occupied even if disconcertingly quiet as if weighed down by its long history. Later I learned from one of its residents that the building was over hundred years old. A window in the side of the corridor looked out on a square shaped opening covered on four sides by walls of other buildings, or maybe by living quarters of the same building. It was difficult to tell from where I stood. It was the reverse of a courtyard; here the back portions of living quarters enclosed the space while their front portions opened along corridors on each floor. Pigeons walked about on sheets shading the windows. Someone had strung hemp rope across the vertical bars which I suspect was to keep the pigeons out. It was cool where I stood. Standing there I could smell the years gone by.

I recollected the conversation I had the previous day with Shantilal Patel when visiting the building with a friend while we were looking for Sookaina Manzil in Masjid. I was curious to find out if the 3, Sakina Manzil from the play of the same name by Jamini Pathak actually existed. It did, though by a slight variation in its name as we found out later that day when we came face to face with Sookaina Manzil near the post office where the postman, Salve, was tolerant enough of me while I climbed up on their sorting table to look up buildings on a map on the wall while he waited down as I read him names off the map. The sorting table had swayed alarmingly under my weight. The next day I returned to Masjid, alone, to meet Qurban Ali. Shantilal had asked me and my friend in the course of a conversation about the 1944 SS Ford Stikine explosion that had rent the dockyard area asunder, if we remembered EC TV. His former work-place was near the EC TV manufacturing unit in Bombay he said. We were conversing by the staircase near the balcony that went from being four feet wide before the explosion of the ship to two feet after the smoke had settled. “Silver bricks thrown clear in the dockyard explosion crashed into the balcony,” he told us. Two women sat by the open door listening to Shantilal tell us both of those days or what little he remembered of it sixty years later. He was born in May, 1946, two years after the explosion that sunk other ships and killed over 800 people, injuring scores with flying debris. Then he told us about the building. “This building was built by Budda Dosha,” he continued, “a rich Gujrati businessman. He owned many more buildings, over a hundred of them. They were five brothers. After they died, their children finished everything.”

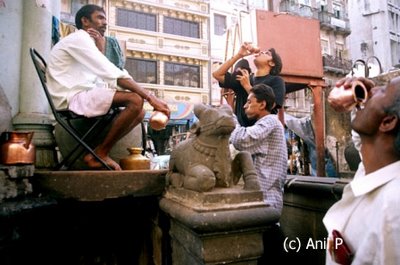

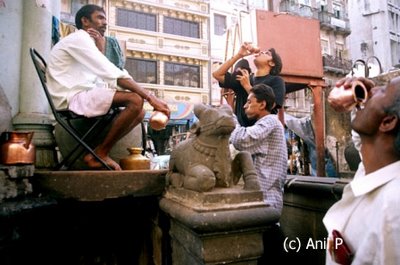

On my way out, I passed the landing where we had met Shantilal the day before. I walked across the Narsi Natha Street in Bhat bazaar to where the fountain stood, a monument in stone where, the previous day, a man in green vest was filling water in shiny brass pots from a drum shaped water carrier fixed to a haath gaadi(hand cart).

Later he joined some acquaintances on the platform where they shared a joke while Nandi sat silently facing the street. On a marble plaque fixed near the bottom of the fountain structure was written in clear letters:

The Kessawjee Naik Fountain and Clock Tower.

Erected by Kessowjee Naik & Son Nursey Kessowjee at a cost of rupees 23000 and presented to the city of Bombay for the use and benefit of the public was opened by His Excellency The Honorable Sir Philip Edmond Wodehouse, K. C. B Governor of Bombay on the 8th day of January 1876.

Designed by R.G. Walton, Municipal Engineer.

Sir Philip Edmond Wodehouse was the Governor of Bombay between 1872 and 1877. He died on 25th October, 1887 when he was 76.

Later in the day, on our way to Carnac bunder, before visiting Pydhonie, Bhendi Bazar, Mohammed Ali Road, and Dongri, passing Sandhurst Road station before returning to Masjid, Kurban Ali stopped the taxi as we neared the fountain. We got off. There he told me of how Kessawjee Naik used to sell water from a leather water-carrier in his early days after arriving in Bombay. Later, Qurban Ali told me, Kessawjee Naik built a fortune, and in obvious acknowledgement to the city that helped him find his feet he dedicated the water fountain to the public, and it is over 128 years now of quenching thirst.

I walked past the fountain to what was essentially a chai shop but was named Mahavir Hindu Hotel. Pausing in front of the chai menu on a large board outside the shop, I mulled the choices of chai listed on the board.

Disco chai - 4 = 00

Rajwadi chai - 5 = 00

A1 chai - 6 = 00

Ukala - 5 = 00

Kesri Ukala - 7 = 00

I asked for

Disco chai. The owner welcomed me in where I took a picture before drinking

Disco chai. It tasted different though I couldn’t place my finger on what made it different. He smiled at me. I smiled back. Outside his shop, people sat nonchalantly on a wooden bench, watching the world go by while a truck emptied its load.

The fountain demarcated the narrow playing areas I now picked my way through, dodging children screaming ‘dead ball’ ‘dead ball’. The green plastic ball they were playing with could not have been more alive in the grey surroundings and the heavy silences characteristic of places weighed down with history or age; mostly both. A red plastic stool substituted for wickets.

The previous day these lanes were choc bloc with people, some of whom had stopped by the fountain where a man in a loose fitting shirt with sleeves rolled up to the elbows sat on a folding chair on the fountain’s raised platform, a brass vessel in hand, and filling brass tumblers with water for thirsty passers-by. The man in green vest would pass the man on the chair brass pots filled with water from the water carrier which he placed by the side of the chair to fill the brass vessel that he used in pouring water into tumblers. Behind the fountain was the office of the

Haath gaadi association. Several empty haath-gaadis were parked in front, and some of the

haath gaadiwallahs operating in the area sat on a low platform, talking. There was a relaxed feel to the place.

To the other side of the fountain, barely five metres from the first team, another cricket match was on. This lot was older, but the passion was indistinguishable from the previous lot. Taking a left turn ahead on my way to Kurban Ali’s house across the street, I passed yet another cricket team, the third in less than two hundred metres from the entrance to the bhaat bazaar. Excited cries rent the air as the batsman scored a hit. I smiled to no one in particular as I looked up at the sky and marveled at the vastness of it all.

As I walked past Patel Restaurant, a radio rung out an old hindi tune mere sawalon ka, jawab do. Do naa. I looked in the direction from which the song was floating out and saw a youth in the hotel eating batata wada while another man reclined on his haath gaadion the pavement outside the hotel, his hands crossed beneath his head, eyes open and facing the sky.

Mere sawalon ka, jawab do. Do naa.

I walked past the fountain to what was essentially a chai shop but was named Mahavir Hindu Hotel. Pausing in front of the chai menu on a large board outside the shop, I mulled the choices of chai listed on the board.

I walked past the fountain to what was essentially a chai shop but was named Mahavir Hindu Hotel. Pausing in front of the chai menu on a large board outside the shop, I mulled the choices of chai listed on the board. I asked for Disco chai. The owner welcomed me in where I took a picture before drinking Disco chai. It tasted different though I couldn’t place my finger on what made it different. He smiled at me. I smiled back. Outside his shop, people sat nonchalantly on a wooden bench, watching the world go by while a truck emptied its load.

I asked for Disco chai. The owner welcomed me in where I took a picture before drinking Disco chai. It tasted different though I couldn’t place my finger on what made it different. He smiled at me. I smiled back. Outside his shop, people sat nonchalantly on a wooden bench, watching the world go by while a truck emptied its load. The previous day these lanes were choc bloc with people, some of whom had stopped by the fountain where a man in a loose fitting shirt with sleeves rolled up to the elbows sat on a folding chair on the fountain’s raised platform, a brass vessel in hand, and filling brass tumblers with water for thirsty passers-by. The man in green vest would pass the man on the chair brass pots filled with water from the water carrier which he placed by the side of the chair to fill the brass vessel that he used in pouring water into tumblers. Behind the fountain was the office of the Haath gaadi association. Several empty haath-gaadis were parked in front, and some of thehaath gaadiwallahs operating in the area sat on a low platform, talking. There was a relaxed feel to the place.

The previous day these lanes were choc bloc with people, some of whom had stopped by the fountain where a man in a loose fitting shirt with sleeves rolled up to the elbows sat on a folding chair on the fountain’s raised platform, a brass vessel in hand, and filling brass tumblers with water for thirsty passers-by. The man in green vest would pass the man on the chair brass pots filled with water from the water carrier which he placed by the side of the chair to fill the brass vessel that he used in pouring water into tumblers. Behind the fountain was the office of the Haath gaadi association. Several empty haath-gaadis were parked in front, and some of thehaath gaadiwallahs operating in the area sat on a low platform, talking. There was a relaxed feel to the place.